Geometry is Not About Shapes

A Journey Through Logic, Beauty, and Perspective

Geometry is Not About Shapes: A Journey Through Logic, Beauty, and Perspective

When most people hear the word “geometry,” they think of triangles, circles, and angles. In school, we are taught that geometry is the mathematics of shapes and their properties. However, this definition only scratches the surface. To say that geometry is about shapes is equivalent to saying music is about notes, poetry is about words, or painting is about colours. Yes, these are the mediums, but the essence runs far deeper.

A course I took, NST2049: Geometry and the Emergence of Perspective, has redefined this understanding. Through its exploration of Euclid’s Elements, historical art analysis, and modern perspectives on space, it became clear that geometry is about logic, beauty, and a deeper understanding of the structure of space.

Personally, I was particularly enlightened while doing research on non-Euclidean geometry. Exploring hyperbolic and elliptic geometries was like peering into a dimension of thought that I had never encountered before. It inspired a curiosity about geometries that extends beyond the familiar three-dimensional Euclidean space into realms shaped more by logic and transformation than by measurement and figure.

This curiosity led me to the field of topology — a branch of mathematics that does not concern rigid shapes, but instead properties preserved through continuous deformations. In topology, the outline of a cow is just a very specifically shaped ball and a coffee cup and a doughnut are equivalent because they both have one hole. How mind bending! This counterintuitive equivalence opens the door to a richer understanding of space and form.

In this exploration, we will begin my learning a bit about topologies rich history and underpinnings. Then, we will learn about the mathematical concepts that govern topology as well as some classic examples of key topological structures. Finally, we will also look at some of the real world applications of topology.

An Introduction to Topology and its History

The underlying motivation for topology is that certain geometric problems do not concern the exact shape of the objects involved, but rather, how they are connected or arranged. For instance, from a topological perspective, a square and a circle share fundamental similarities: both can be constructed with a single thread of line and each divides the plane into an interior and an exterior region. This branch of mathematics studies the properties of a geometric object that are preserved under continuous deformations. Such deformations include stretching, twisting, crumpling, and bending while prohibiting closing holes, opening holes, tearing, gluing, or passing through itself.

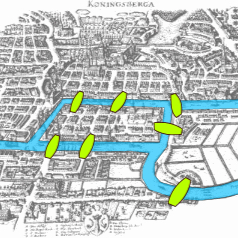

Topology’s origins trace back to the 18th century with the work of Leonhard Euler, who laid the groundwork with his famous proof of impossibility to the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem. The problem was to devise a walk through the city of Königsberg in Prussia that would cross each of its seven bridges exactly once. This result had no bearing on the lengths of the bridges or on their distance from once another, but purely on the connectivity properties like which bridges connect which two riverbanks.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, mathematicians like August Ferdinand Möbius, Johann Benedict Listing, Henri Poincaré, and Felix Hausdorff further expanded the field. Topology gradually emerged as a formal discipline, transforming how we perceive continuity and space. Today, topology is a vital part of pure mathematics and a foundational tool in physics, computer science, and even biology. It challenges our classical perceptions and demands a more abstract yet intuitive way of thinking about space.

Manifolds and Orientability

Topology is such a far-reaching and intricate domain that a single blog post won’t do it justice. Thus, this post will focus specifically on a thin slice of topology, namely “non-orientable manifolds”. Before we continue further, however, let us define what topological orientability and manifolds actually mean.

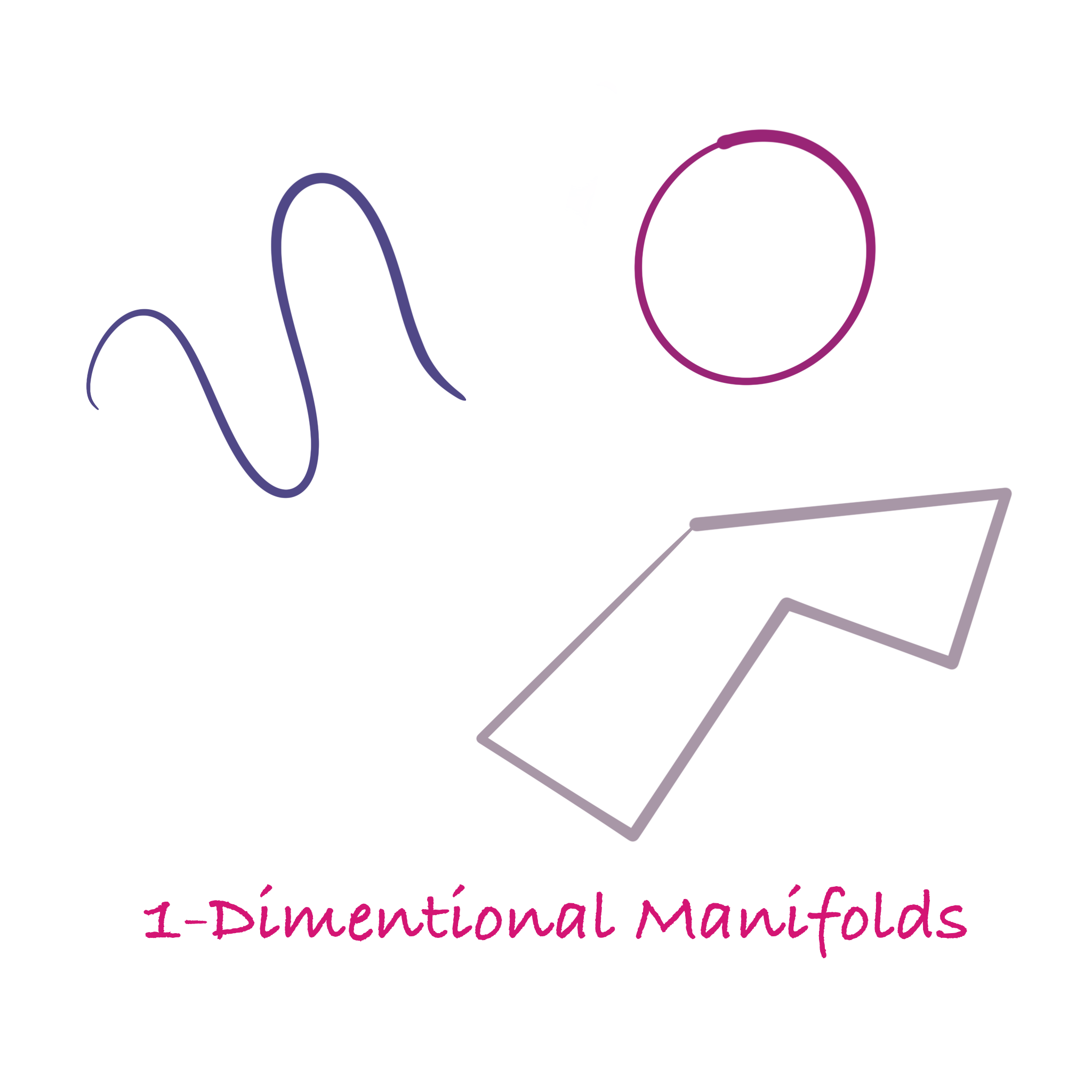

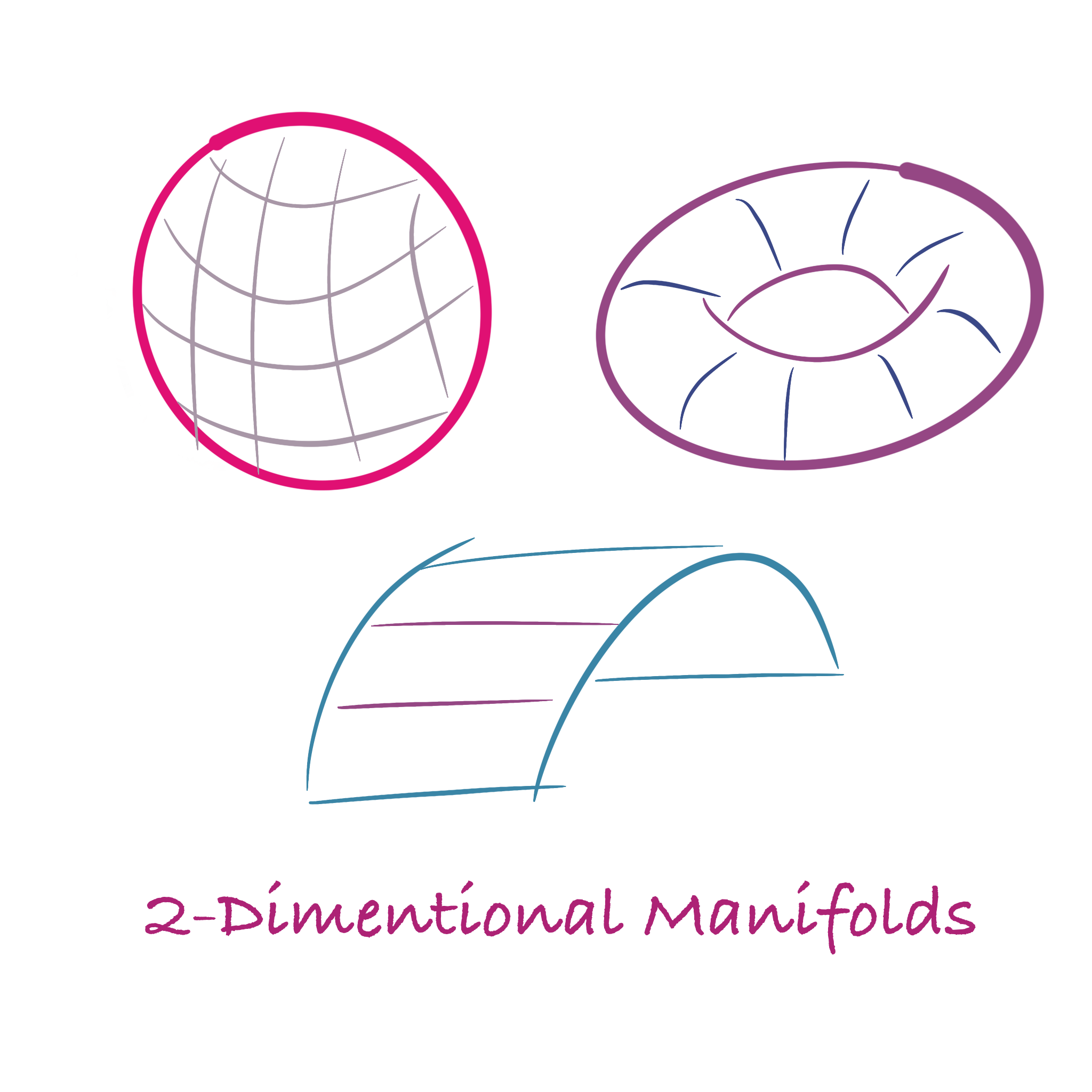

A manifold is a space that locally resembles Euclidean space. In simpler terms, around every point on an n-dimensional manifold, the space looks like the Euclidean space of the same dimensions that we are used to. For example, one dimensional manifolds include curves and circles since when zoomed in sufficiently, the space resembles a 1 dimensional Euclidean line. On the other hand, self-crossing curves such as a figure 8 are not one-dimensional manifolds since at the intersection point, the space exceeds 1 Euclidean spacial dimension. Two-dimensional manifolds are also known as surfaces, which includes the plane, the sphere, and the star of today’s show (drumroll please) — the Klein bottle.

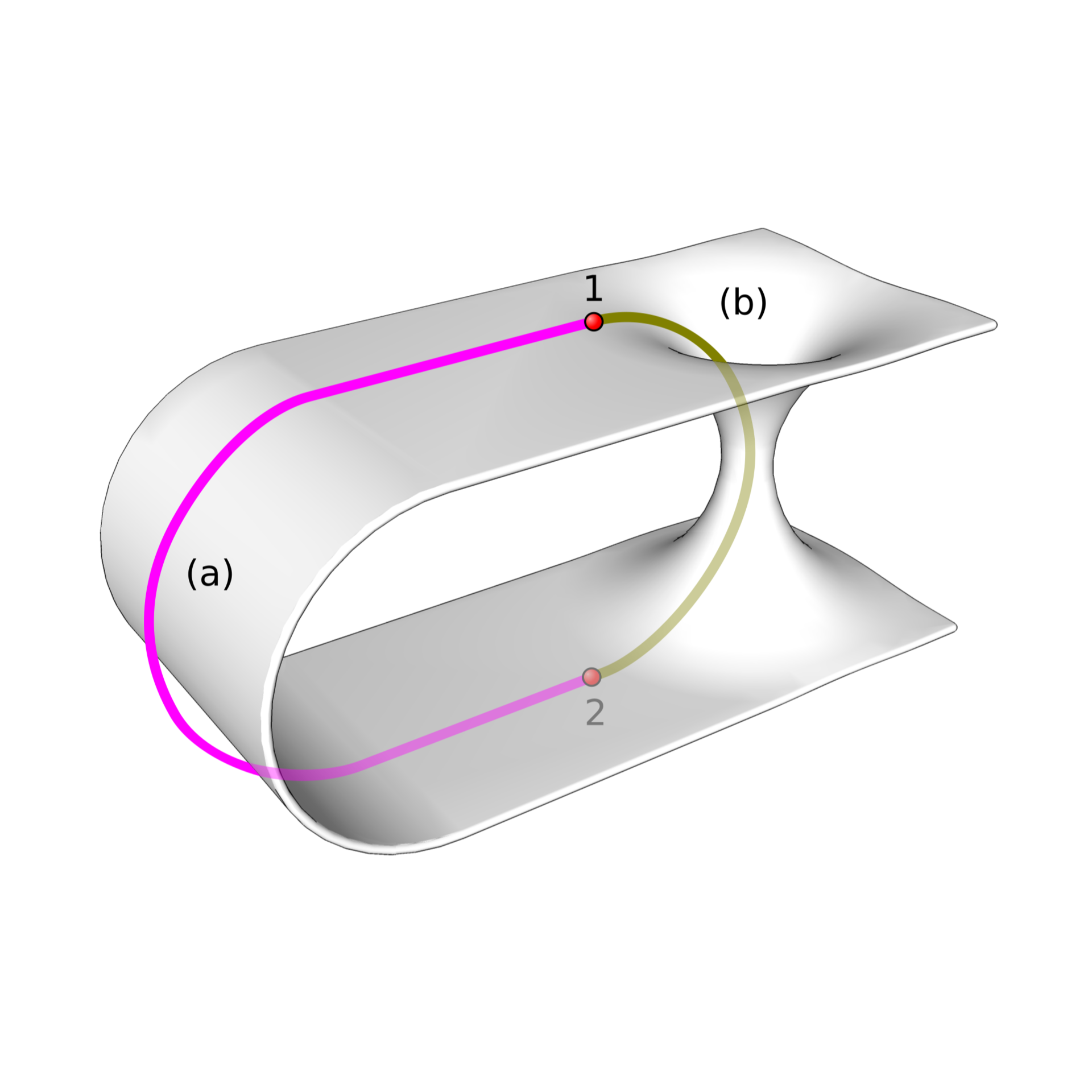

One important property of manifolds is orientability. Intuitively, a manifold is orientable if you can consistently define a direction across its surface. Imagine walking along the manifold with a small arrow that is perpendicular to the surface and points directly upwards from your head at all times. If you can move around any loop and return to your starting point without the arrow flipping, the manifold is orientable. If the arrow flips after some loops because you are now standing on the other side of the surface where you began, the manifold is non-orientable.

With these newly equipped knowledge, let us delve into the fascinating world of non-orientable manifolds!

The Möbius Strip: One Side, One Edge

A Möbius strip is the simplest example of a non-orientable manifold. You can construct one by taking a strip of paper, giving it a half-twist, and taping the ends together. What results is a manifold with only one side and one edge.

To understand its non-orientability, imagine drawing a line along the middle of the strip without lifting your pen. After a while, your pen will reach the point where you began, except, it will be on the “opposite side” of the surface. If you continue drawing, eventually you’ll come back to exactly where you started and you’ll have drawn on both sides of the original paper. This means that the concepts of “side A” and “side B” for the underlying piece of paper break down completely.

The Möbius strip shows us that even something as seemingly simple as “edges” is a topological property, not an inherent truth of physical space.

The Klein Bottle: A Seamless Surface Without an Edge

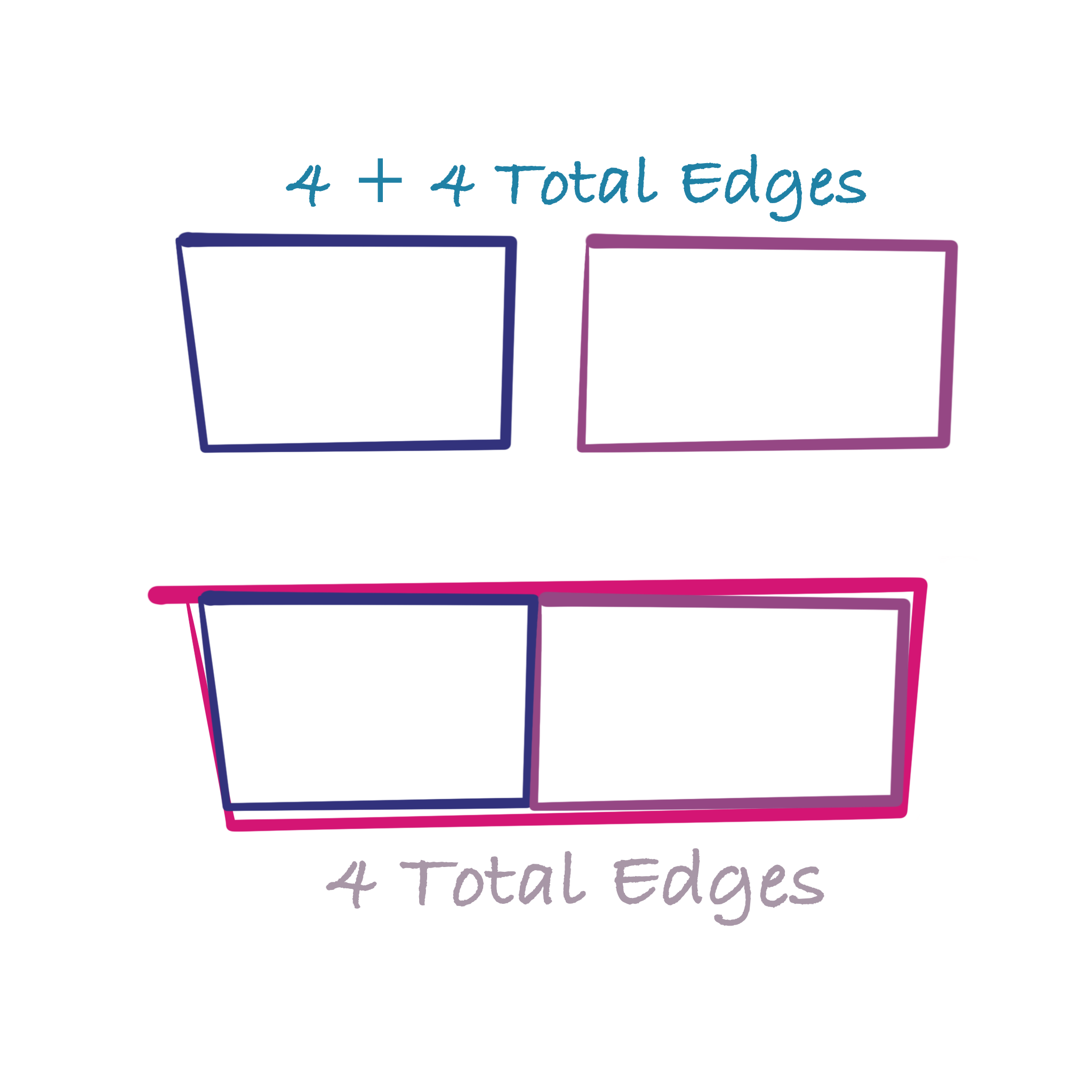

It is a mathematical fact that if we stitch two shapes along a common edge length, the overall number of edges will decrease. For example, take two squares with the same edge length, the total number of edges when they are separate is 8. After we stitched them together along one of each of their edges, the total number of edges reduces from 8 to 4.

Now, let’s go a step further. We’ve previously established that a Möbius strip only has one edge… but what happens if we stitch two Möbius strips together along their only edge? We get the Klein bottle. This is a more complex non-orientable manifold. It has no more edges, and just like the Möbius strip, has only one surface.

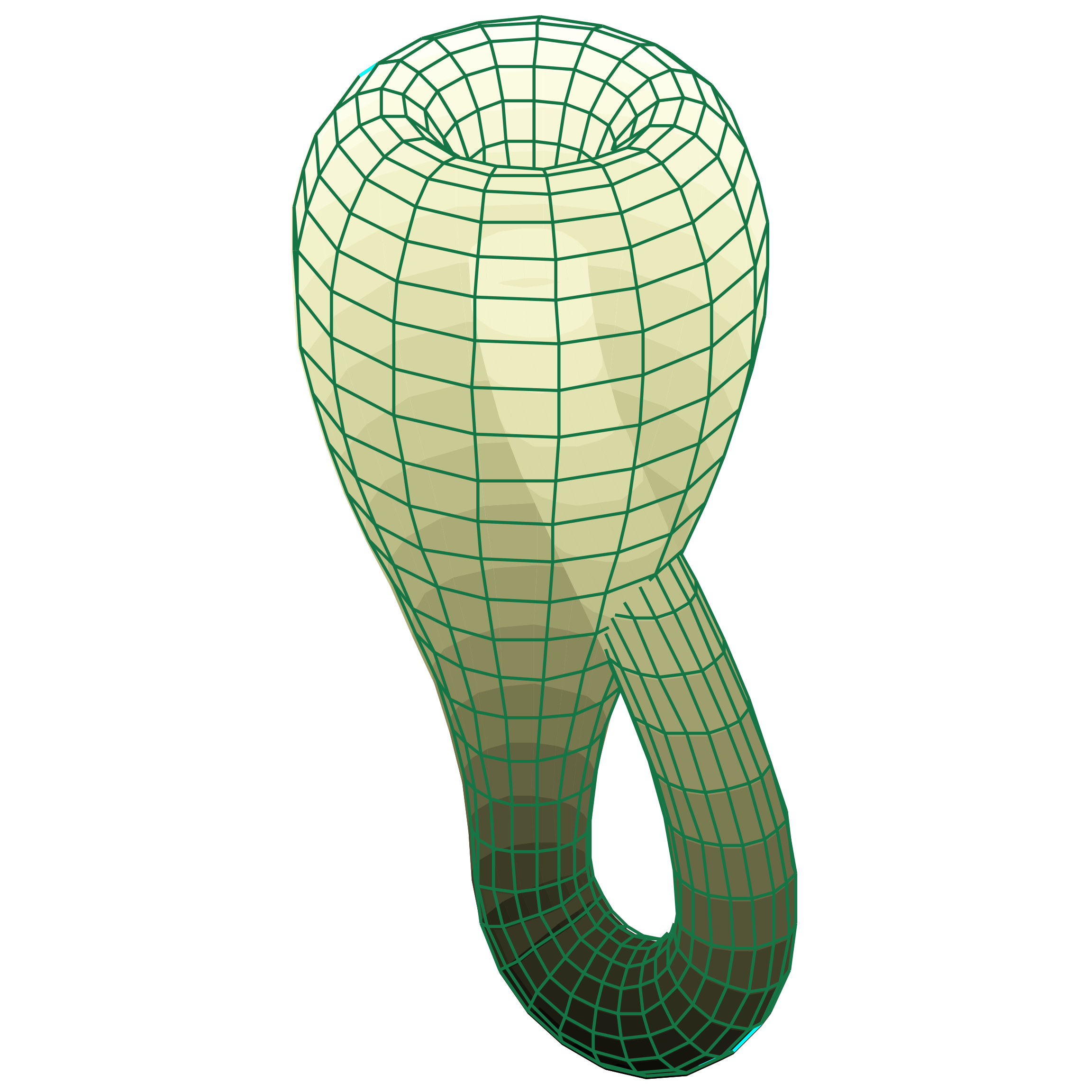

The Klein bottle was first described by mathematician Felix Klein in 1882. The construction of the Klein bottle is equivalent to taking one end of a cylinder and feeding through itself to connect to the other end from the inside. Here is a neat little animation to help you better visualise this:

Since the Klein bottle has just one side and no edges, an ant crawling on the bottle can reach any surface (both inside and outside) of the bottle without ever crossing and edge.

However, the Klein bottle cannot be embedded in three-dimensional Euclidean space without the strange looking self-intersection. To properly visualise it, we will need four spatial dimensions. It defies our spatial intuition and further reinforces the idea that geometry is more about properties and relations than it is about visualising shapes.

The Real-World Relevance of Topology

So why does any of this matter outside of an academic context? Well, topology actually has a surprising number of real-world applications.

Mathematical Physics: In quantum field theory and general relativity, the topology of space-time can influence the behaviour of particles and the structure of the universe. Concepts like wormholes, topological defects, and string theory are deeply grounded in topological reasoning.

Computer Graphics: Modern rendering engines use topological data structures to simulate realistic surfaces and deformable objects. Whether it’s creating the twisting folds of a character’s clothing or morphing objects in animated films, topology helps ensure that transformations are smooth and logical.

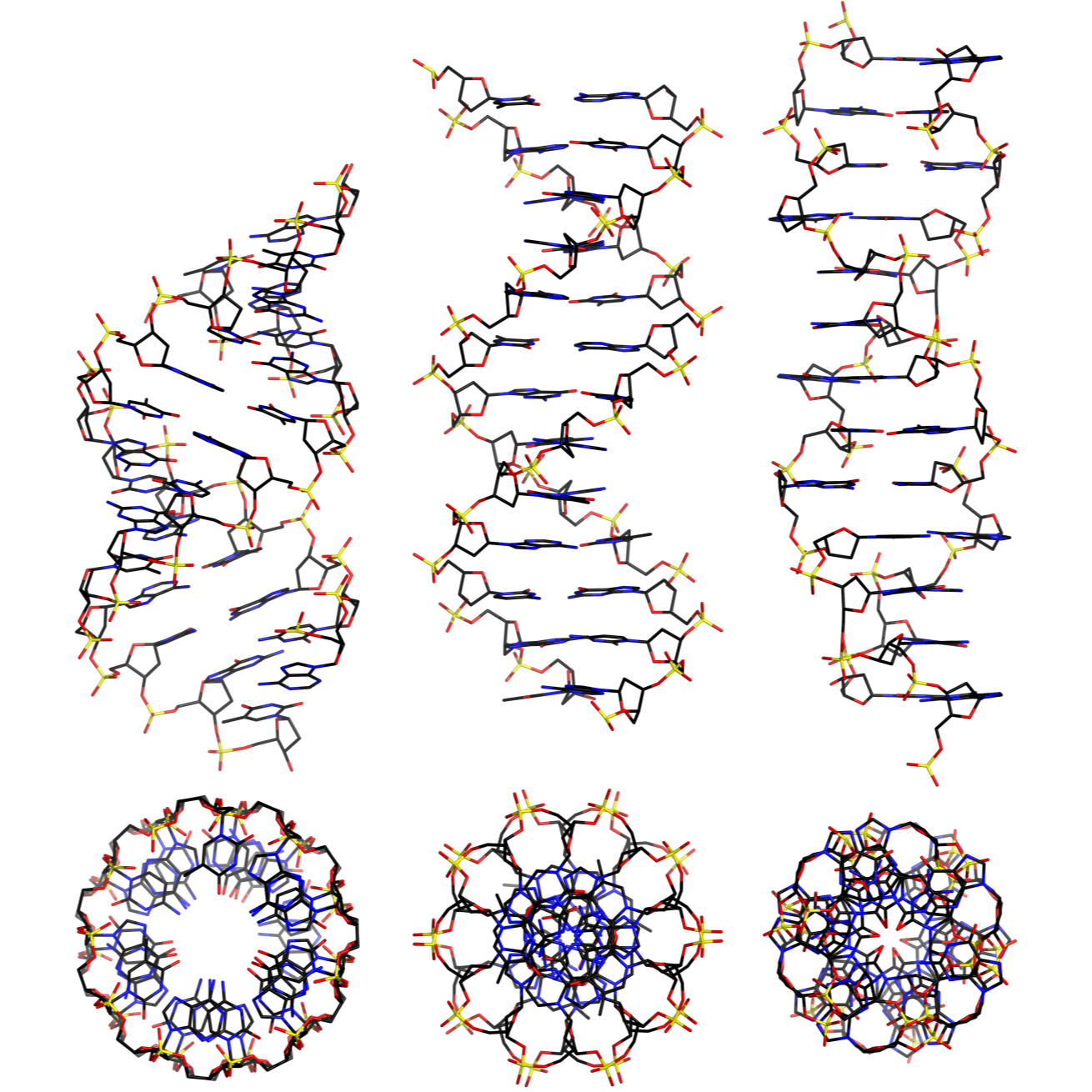

Biology: In molecular biology, the shapes of DNA and protein folding are studied using topological concepts. Understanding knots and links in DNA, for instance, is critical to comprehending how genetic information is stored and transmitted.

Robotics and AI: Topological data analysis is increasingly used in machine learning and robotics to extract features from high-dimensional data, plan motions, or even understand the shape of data spaces.

Conclusion: The Shape of Thinking

Through this exploration, I hope I have convinced you that geometry is not about shapes in the narrow sense. It is about patterns, structures, and the logic that binds them. It is about understanding how we see, move through, and interpret space. When you see a Möbius strip or hear of a Klein bottle, you’re not just encountering a quirky mathematical object. You’re witnessing a powerful abstraction of how space can be twisted, turned, and connected in ways that defy ordinary experience. You’re seeing geometry at its most imaginative, its most beautiful. And that, perhaps, is the real shape of geometry: not triangles or circles, but ideas that bend the very space in which we think.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my instructor, Professor Francesca Spagnuolo, and my fellow classmates of NST2049 for the amazingly meaningful and insightful discussions. Without whom and which, the completion of this work would not be possible.

Works Cited

Unless explicitely cited in the caption, all images used in this exploration are either hand-drawn by the author or is licensed under the Creative Commons license.

Wikimedia Foundation. (2025, March 24). Klein bottle. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klein_bottle

Wikimedia Foundation. (2025, April 16). Manifold. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manifold

Wikimedia Foundation. (2025, April 5). Orientability. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orientability

Wikimedia Foundation. (2025, April 7). Topology. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Topology